Editor’s Note: The trilogy and tetralogy are commonplace in genre fiction: science-fiction, fantasy, mystery. But what of literature? Tori Merkle dissects the phenomenon and helps us understand its often unrecognized significance, not only in storytelling but in an author’s oeuvre.

Literary Chronicles:

An Exploration of Trilogies and Tetralogies in Literary Fiction

by

Tori Merkle

It’s a fact of storytelling: chronicles sell. Series novels, commonly a trilogy or tetralogy, are especially popular in genre fiction—we sit waiting and watching for the next sci-fi or fantasy saga to top the bestseller list and then hit the box office. Once we get the first luscious taste of a fictional world, we’re ravenous for more. We become attached to the characters as if they’re intimate friends. We’re eager to know what happens next. This is the same energy that fuels the television/streaming binge-watching phenomenon; we are immersed—obsessed, even, with our fictional retreats, and we want to prolong our stay.

Behind it all is our natural discomfort with the unknown and the attendant thirst for knowledge. Fiction allows us to see the entire scope of a story—enclosed, tidy, and complete. We turn the pages and follow the threads of cause and effect, sometimes all night long. We’re witness to how the drama began, unfolded, and ended. We’re the all-knowing overseers, and there is a strange power in that—a super-power that we could never have in our own lives. It allows us to observe and speculate on a grander scale, like watching the entire lifespan of an amoeba in a science lab. A character is the closest replica we have to a human, and in the frame of a novel he or she becomes our experimental subject.

Given this immense impact of fiction, it makes sense that we become voraciously frustrated when the story doesn’t feel finished. What would have happened next? Serial genre fiction enables us to learn and follow the rest of the story. But a series can also play out in literary fiction, which we will term literary chronicles. They possess the same delight.

Because characters in literary chronicles are merely mortal, there is often greater rapport for us, the readers, in their episodic nature. Like them, we live in chapters—weeks, months, years, decades, stages of life, sometimes mirroring a character’s passage from infancy to senility. We love to ponder each of these stages and see how they connect, measuring and analyzing how much we, too, have changed, what we’ve learned, what great failures and accomplishments mark various episodes in our lives. We journal, scrapbook, take photos, tell stories; we’re constantly documenting our lives and looking upon our archives with the bittersweetness of nostalgia. Doesn’t it make sense, then, for our fictional counterparts to exist similarly? Sure, every novel has some sort of chapter structure, but a chronicle of novels offers an additional lens through which to see the story. Fiction is our mirror, and the chronicle captures a larger and more complete picture. A story that covers more time and space adds more dimensions to the characters. There is more potential for plot twists that uncover new depths of the characters and their responses to their world. Thus, when it comes to telling a more realistic human narrative, literary chronicles are more satisfying.

We’ve seen plenty of genre fiction take advantage of the multiple-volume saga with mountainous success. Trilogies and tetralogies exploring sci-fi, fantasy, mysteries, or dystopian worlds dominate popular YA fiction and adult fiction alike. Many go beyond three or four books, seeming to continue interminably with new narratives and timelines. These sagas are driven by the world-building, networks of characters, and action-filled plots that make for an endless number of possible stories to tell. J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings series started with The Hobbit and built upon itself into an elaborate high fantasy world. J.K. Rowling began by imagining a beginning and end of the Harry Potter series and warped the story along the way as her fictional world developed and changed. With the Fantastic Beasts movies, she’s currently backtracking and telling the story of what happened before the eight books in the main series—demonstrating the potential of the saga, as has George R.R. Martin with his A Song of Ice and Fire.

These genre sagas have layers and layers of details, characters, and timelines that create the universe in which they exist. Once this imaginary world is created and published, it is immortal. The sagas can continue indefinitely with new casts of characters and timelines. They collect healthy fanbases that carry the stories to film, television, theater, video games, and graphic novels, saturating pop culture. We love these stories and become addicted to the escape from reality they offer. We connect with the characters and let the fascinating plots push and pull our imaginations. Can chronicles do the same for literary fiction, with its smaller scale, fewer characters, and more contained plots?

Literary Chronicles of the 20th and 21st Century

When there aren’t wizarding schools, magical realms, and dystopian governments to explore, the chronicle becomes a deep exploration of the way humans in our world think, change, and interact. Often, literary trilogies and tetralogies follow the extended growth and development of a character, acting as long and detailed examinations of mentality and behavior. The works of John Updike, Rachel Cusk, and Philip Roth exemplify this depth of character. A trilogy can also capture a volatile or transitional historical or cultural moment in its complex entirety, perhaps more successfully than a single novel can. Such is the case in the works of Philip Roth, John Dos Passos, Pearl S. Buck, Ken Follett, and John Galsworthy. Each of these writers uses the literary chronicle in a different way, all to their advantage.

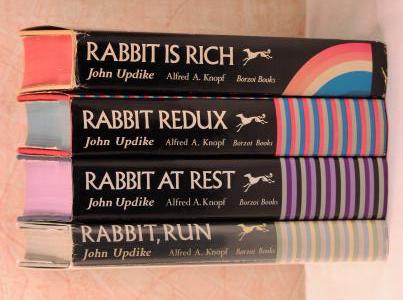

John Updike’s Rabbit Angstrom Tetralogy

John Updike’s tetralogy, beginning with Rabbit, Run and continuing with Rabbit Redux, Rabbit is Rich, and Rabbit at Rest, follows Rabbit Angstrom through his adulthood and gives us an intimate view of his inner world—and how he defines his outer world. In Rabbit, Run we are introduced to Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, a suburban everyman. We see how his affair inevitably leads to the downfall of his marriage. In the subsequent novels, Updike’s protagonist goes from working as a Linotype operator and living in a commune to maintaining a life as the wealthy, married owner of a car dealership to retiring and being eaten away by depression and obesity. Rabbit dies just after resolving his personal conflicts, bringing the tetralogy to a finite close. Through the sequential novels, Updike traces the complete downfall of a man, effectively portraying the way his life evolves and devolves. We are always right alongside Rabbit Angstrom, witness to his dimwitted personality and poor decisions. Rabbit is not a good man, but his character is explored in depth nonetheless and we get a portrait of who he is and what he’s done with his life.

Rachel Cusk’s Outline Trilogy

Rachel Cusk’s trilogy, too, is an exploration of character. One crucial difference between Updike’s tetralogy and Cusk’s trilogy is that Cusk maintains a level of separation between the reader, the narrator, and the other characters of the novel. Faye, the central character in Outline, Transit, and Kudos, is a novelist, a listener, and a recorder of stories. The novel is told through stories of her conversations and experiences. A writer is by nature observant and critical—she must be in order to capture the human experience. In showing us the world through this lens, Cusk’s trilogy explores character development on an exceptionally deep level. Not only do we see people and society through the novelist-character’s lens, but how the novelist’s personality and life are evolving through Cusk’s lens. Though the portrait is piecemeal and restrained, it creates the sensation that we are Faye, and we are almost experiencing her career and personal dramas just as she is. We become invested in her as we are invested in ourselves—the difference being that to know what happens to Faye next, all we have to do is continue reading the rest of the chronicle. Each novel is set in a different moment of Faye’s life, and their chronology demonstrates how each leads to the next. In that sense, the second novel is appropriately titled—the chronicles show us Faye in transit from one phase of her life to the next.

These literary chronicles give us an intimate view of characters and track their growth and development in a way that both mimics our reality and gives us a level of access to another’s human experience that we cannot experience in the real world. Rather than showing us only a singular time of a character’s life, Updike’s tetralogy and Cusk’s trilogy show us what a particular moment looks like, how the phases of a character’s life are connected, and how the character develops—or perhaps does not—throughout their life.

Other literary chronicles, such as those we examine next, go beyond a character study to explore a period of history or the broader aspects of a particular culture through the characters’ eyes.

Philip Roth’s American Trilogy

Philip Roth’s American trilogy, comprised of American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain takes us into the personal and interior lives of characters through their times of success and turmoil. Like Cusk’s work, the separation of protagonist and narrator in the first novel of Roth’s trilogy, American Pastoral, creates a biographical, journalistic tone. Roth’s narrator, too, is a writer, telling the stories of other people. Each novel is an exposé on its characters, painting a revealing portrait. The narrator, Nathan Zuckerman, is literally digging for information on his subjects and how they came to be where they are. Zuckerman’s eye is inquisitive and analytical, attempting to learn as much as he can about a person and develop the truest portrait. The real inquisitor, of course, is Roth.

Philip Roth’s American trilogy, comprised of American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain takes us into the personal and interior lives of characters through their times of success and turmoil. Like Cusk’s work, the separation of protagonist and narrator in the first novel of Roth’s trilogy, American Pastoral, creates a biographical, journalistic tone. Roth’s narrator, too, is a writer, telling the stories of other people. Each novel is an exposé on its characters, painting a revealing portrait. The narrator, Nathan Zuckerman, is literally digging for information on his subjects and how they came to be where they are. Zuckerman’s eye is inquisitive and analytical, attempting to learn as much as he can about a person and develop the truest portrait. The real inquisitor, of course, is Roth.

Roth’s trilogy is more thematically connected than anything else, each book focusing on different characters: the father of a terrorist, a former radio star married to a closet communist, a black college professor purporting to be white. This brings another level of analysis to the work—rather than telling an individual’s story, Roth is telling the story of a country and a culture. The trilogy focuses in on some of America’s tensest decades, when anti-war, anti-Communist, and racist sentiments were especially pronounced in American culture. It explores the common threads between the intellectual movements and vulnerabilities of America. Each of the novels in Roth’s chronicle paints a picture of how history, background, and politics get entangled, either willingly or unwillingly, with the lives of individuals.

Here are examples of literary chronicles which best capture a period of history or the nuances of a particular culture.

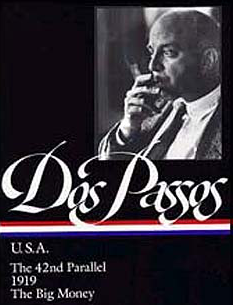

John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. Trilogy

Dos Passos highlights an American era rife with change in his U.S.A. trilogy. The three books (The 42nd Parallel, 1919, and The Big Money), cover three decades of the early twentieth century. Unlike Roth’s chronicles, Dos Passos’s trilogy is set in chronological order, spanning from the leadup to World War I to its aftermath, and has a consistent cast of characters. Rather than crafting a thematic catalog of America, such as Roth’s, Dos Passos tracks how history unfolds and complicates the lives of his characters over time. In that sense, while both trilogies are artifacts of history and culture, they take very different approaches. Roth’s novels are distinctively personal; Dos Passos’ employ a broader interpersonal perspective. Dos Passos structures his novels around cause and effect—how things go wrong, correct themselves, and build upon each other to create what we know as history.

Pearl Buck’s Good Earth Trilogy

What Dos Passos does for war-torn America, Pearl Buck does for rural and revolutionary China. Buck’s trilogy, comprised of The Good Earth, Sons, and A House Divided, is centered around a farming family in China at a time of political unrest during the early twentieth century. Buck’s chronicle is similar to Dos Passos’s in that the first book is set before the revolution, the second book opens as the revolution dominates China, and the third book captures the aftermath of the rebellion. Buck also paints an intimate picture of a growing and changing family, making her trilogy a twofold portrait of human existence. As China’s political scene changes, so do the lives of her characters, who are beset by poverty, oppression, and the specter of world war, to name but a few of their problems.

These chronicles are both expansive and contained. Each goes beyond what can be told in one book, but the stories do not continue indefinitely. The individual books of these chronicles could be thought of as chapters in a single volume, expressing a more comprehensive (and perhaps empathetic) view of history for the reader. While Roth’s trilogy highlights specific American tensions occurring individually over a few decades, Dos Passos and Buck capture continuing or connected transitions within their country’s cultures. Dos Passos and Bucks’ chronicles are neatly packaged— one book focused on the time before the significant historical event (war or revolution), one book during it, and one book after. Roth’s novels are more loosely connected, but each remains relevant to the others and contributes to the grander theme of humanity’s stains on history. In either case, the chronicle format seems not simply appropriate but necessary.

Dos Passos and Buck are not the only authors to take advantage of the apparent power of three. Ken Follett and John Galsworthy have both demonstrated success writing trilogies—and not just one.

Ken Follett’s Century Trilogy and Kingsbridge Series

Ken Follett has written two imaginative and wildly popular historical fiction trilogies. His jump from international intrigue to historical fiction began in 1989 with The Pillars of the Earth, the first novel in his Kingsbridge series that traces the building of a church in the twelfth century. The sequel, World Without End, was released in 2007, after which he published his second historical trilogy, the Century trilogy, before finishing the Kingsbridge series with A Column of Fire in 2017. Although the Century trilogy (Fall of Giants, Winter of the World, and Edge of Eternity) is set in the twentieth century and highlights five different countries, and the Kingsbridge series is set in the 1500s in just one fictional European city, both are elaborate works of historical fiction. The chronicle format of these novels is perhaps what accounts for their success—after reading a first novel, fans can (and may in fact be eager to) come back for more.

While Follett might very well add to the Kingsbridge series, it is interesting to note the lengths of time between his novels and the wholeness of the Century chronicles at three books. In the trilogy, Follett tells a story that feels complete. By following historical eras, he identifies a natural beginning and end for the story, all the while painting a portrait that is thorough in its exploration of character and contained within the span of the trilogy. Having a slow pace when it comes to publishing, Follett can do the same with the Kingsbridge chronicles—telling it chapter by chapter to a satisfying conclusion. To know when to stop has to be one of the more aesthetic decisions a chronicle author must make.

John Galsworthy’s Forsyte Saga

Galsworthy’s Forsyte saga, or chronicle, also uses the trilogy to build upon and complete a story about an upper-middle class British family. In this case, the chronicle is comprised of three complete trilogies: The Forsyte Saga, A Modern Comedy, and End of a Chapter. Each trilogy offers a sense of completion in itself, and each subsequent trilogy reopens the story and completes yet another continuing chapter. Galsworthy even goes so far as writing interludes to bridge the gaps between the trilogies, demonstrating just how flexible the literary chronicle is. The novels are connected through character and plot, allowing Galsworthy to track the evolution of individuals and history over large amounts of time. This kind of flexibility is both useful and dangerous for a writer. Multiple characters adds richness to the portrayals, but too many and the reader cannot remember them and their actions. The same pitfalls can occur as time passes, for history cannot be told without a certain degree of expansion and compression; this can create a false sense of the story’s inevitability being determined by the author’s hand.

The Flexibility and the Risks of a Literary Chronicle

The Mahabarata (ca. 900-800BCE], ascribed to an Indian guru, may be the longest and oldest multi-volume narrative ever written.

There is no doubt that each of these authors takes an interesting approach to storytelling by recognizing the value of a chronicle. Writing a chronicle grants writers the flexibility to tell a story and build a world until they and their readers are satisfied. The chronicle more closely mimics real life in that no chapter is closed and tucked away—there is always room to reopen an event and continue building upon the story. A sequence of books can warp and bend with the ever-changing lives and settings of its characters. No life is stagnant and neatly packaged, so why should a novel’s portrayal of one be so? Given the constant movement and evolution of human existence, a series of novels makes sense. But if that’s true, why don’t all series continue indefinitely?

Along with the seemingly endless potential to extend a chronicle comes a kind of danger. One of the joys of reading a chronicle is that you get to spend more time in a fictional world that you’ve already become very fond of. Such worlds can be sad to leave—we might continue the stories in our heads, resulting in the swarms of fan fiction on popular series, but it is not the same when we run out of pages to turn. Our mental movies come to a halt—sometimes a startling and unsettling one. I can recall many times, in reading a series, that I longed bitterly for another chapter. What happens to those characters whom I love so much? Do they just disappear, dissolve like dandelion fuzz and vanish into the breeze? On the other hand, it might be tempting to keep the story rolling forever. Beyond the reader’s feelings and satisfaction is the mindset of the publishing industry behind it: if demand is strong, there is still potential to supply it and make more money. For the writer, there can also be an existential crisis—having worked in a fictional world for so long, how does one stop?

Yet, the second joy of reading a chronicle is that it feels complete. The story is extensive, but eventually it must come to a conclusion. We put the last book down and feel a sense of satisfaction—we’ve absorbed this story, hung on with it as it changed and developed, and now we get to step off the ride and look back on how far we’ve come. It gives us that exclusive, all-knowing feeling of satisfaction we can never obtain in our own lives. It’s not unlike the wisdom of an old man who can sit upon his deathbed and reflect on each chapter of his life, all of the ways he’s changed, all of the changes he’s seen in his environment. Yet a literary chronicle is even more satisfying, because in reality we can never witness our own final turn of the page.

This sensation is important. For a series of novels to work, it has to hit the reader’s sweet spot. It must continue long enough to fulfill the story’s potential, and it must know when to stop. Therein lies the challenge and potential of a good literary chronicle. While there are many wonderful and wildly popular series in genres such as fantasy and sci-fi, from Harry Potter to Percy Jackson, a long saga of eight or ten books may not be as suitable for literary fiction. Just as we tend to organize and recall our own accomplishments, growth and achievements, we tend look for the same patterning in a fictional portrayal of a person or a time period. A single novel has a very finite story, but chronicle-authors like Updike give us that long-term patterning in Rabbit Angstrom, as does Dos Passos in his documenting World War I and its impact.

That is why, for a work designed to mimic or capture what it is to be human, it is often best to be both elastic and finite. A singular novel is not always satisfying—it might present a fantastic story, but there are always untied threads that could lead to other stories. No identity can be adequately captured in a freezeframe. Yet a lengthy series can also be dangerous if it does not provide a sense of completion and resolution.

Our lives are always changing, but we still want to step back and look at our experiences in chapters and feel like we’ve completed some arcs of development. Literary chronicles of three or four novels achieve both of these things—they can stay true to ever-changing human nature while providing a greater depth of insight into the spectrum of human stains.

***

Victoria “Tori” Merkle is a junior at Wellesley College, majoring in English and creative writing with a minor in anthropology, and an editorial assistant at Joshua Tree Interactive. She is author of the novella “Elephant Tadpoles,” which debuted here [in three parts] recently.